This is a reprint of the article that was published in Daily Yomiuri on March 13, 2004.

Wataru Doi Special to The Daily Yomiuri

A few minutes walk from the East Exit of JR Ebisu Station in Tokyo leads one to a restaurant that is a bastion of old-fashioned male eating habits. Packed with salarymen and laborers, the restaurant is located near a corner tobacco store, a traditional tatami shop and an old grocery in an antiquated patch of Ebisu that does not fit the district's stylish image.

It is lunchtime, and all the customers at the restaurant seem to be middle-aged men pressed for time. The place, Kozuchi, is a teishoku-ya (set meal restaurant) famous among men working in the area. Kozuchi is situated on the ground floor of a multi-tenant building near the well-known Yebisu Garden Place complex.

"What'll it be today?" a waiter urgently asks, even though his salaryman customer has barely opened the door.

"Shogayaki (ginger pork) teishoku," the customer quickly responds before taking a seat. A couple of minutes later, a set lunch of steamed rice, miso soup and fried pork with ginger and cabbage appears on the counter in front of the customer. As he launches into his lunch, the waiter places two 100 yen coins and a 50 yen coin on the counter.

The instant the customer finishes wolfing down his meal, he grabs the coins and slaps a 1,000 yen bill on the counter in their place, while readying himself to dash off back to work.

"We've been running this teishoku-ya since 1950 right here," says Masao Oishi, one of the oldest staff at Kozuchi. "In the past, there were loads of teishoku-ya around here, but now there are hardly any. We serve food that is the staple fare of typical Japanese households and in this way we provide support for busy male

workers."

For young people, Ebisu is a good place for lunch. After Yebisu Garden Place opened in 1994, this beer-producing district became a symbolic trend-setting spot in Tokyo. Today's Ebisu is filled with stylish restaurants and swanky cafes that appeal to voguish people and gaishi (foreign investment company) executives.

However, for middle-aged salarymen, who were the "warriors of corporate Japan" during the nation's high-growth period, Ebisu may not be such a convenient place. While fast eating and lightning toilet breaks were once considered part of an employee's "talents," many would now find it difficult to grab a quick bite in Ebisu. Many

restaurants here focus on attracting young female employees, a clientele that considers an hourlong lunch break an important part of the working day.

"Kozuchi is a valuable place for people like me. As long as Kozuchi exists, Ebisu is not a bad place," says the shogayaki eater. "I think Kozuchi is a male sanctuary in Ebisu."

Kozuchi does in fact pride itself in being something of a shrine to the institution of the male lunch break.

"Let me talk frankly," Oishi says. "These days, women sometimes come here for lunch. But we don't really like young women who come here and spend ages deciding what to eat, let alone eating it. They sometimes hang around for a chat with their friends after they have finished.

"We suggest that these customers go somewhere like a fashionable Italian restaurant."

Photos by Wataru Doi

Regular patrons hurriedly down their lunches at popular teisyoku-ya Kozuchi in Ebisu, Tokyo.

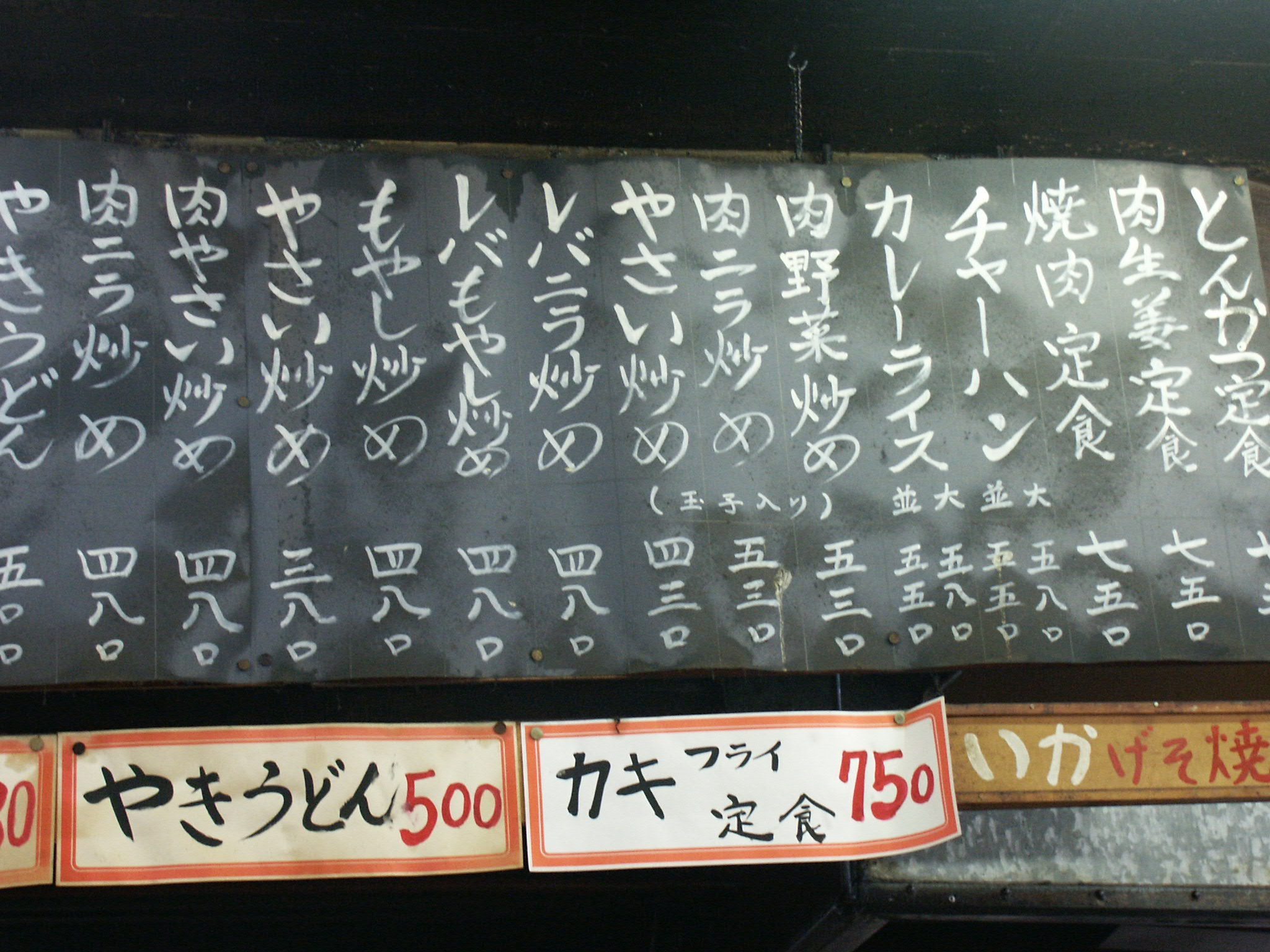

Kozuchi's menu offers variety of choices.

Kozuchi's flavorful yakiniku teishoku.

Another customer--male, of course--nods twice to indicate he is about to order. He chooses the 480 yen teishoku of the day, consisting of rice, miso soup, and fried horse mackerel with cabbage.

According to Oishi, Kozuchi serves 200-300 customers a day. Most of them are middle-aged male workers--and regulars.

"We serve big portions to hungry people. Women can't even finish our servings," he says.Another men's place in Toranomon

"To tell you the truth, we're not overjoyed when we get female customers," says Kiyoshi Nishimura, the owner of Mimura, another bastion of speedy male eating. "In the time it takes one woman to decide what to order and eat it, two men could have finished (their meals)."

Mimura is located in Toranomon, the center of the nation's governmental district, which is also home to many companies. Mimura has been serving teishoku to businessmen and public officials since 1966.

"Due to its location, eight out of 10 customers are typical middleaged Japanese salarymen," Nishimura says. Like at Kozuchi, most customers go there alone and wolf down lunch without saying a word. The difference is that Mimura serves only fish dishes.

For lunch, Mimura offers only teishoku priced at 900 yen. The menu includes rice, miso soup, oshinko pickles, raw egg and a choice of grilled fish (mackerel, saury, herring, flounder or redfish) or stewed fish (mackerel, alfonsino or flounder).

Not all teishoku-ya focus on accommodating men in a hurry. To help expand their customer base, emerging teishoku chains are keen to attract females. According to Otoya, the nation's biggest teishokuya chain, while their traditional customer base was businessmen and single male students, an increasing number of women and families have started going to the chain.

But for independent teishoku-ya such as Kozuchi and Mimura, the chains represent a threat. While neither store intends to compromise its approach to survive, Oishi acknowledges that the chains can provide cheaper meals.

"Unlike chains, we have to generate our revenue based on 20 days of business a month because we do not open on weekends. This is very tough for a restaurant business," Nishimura says. To become more profitable they have to improve turnover, he adds.

Female customers may not always be welcome, but Kozuchi and Mimura are, in fact, attracting more of them. Oishi said the reason is the familylike atmosphere of a teishoku-ya, the kind of atmosphere that existed in Japanese households in the past.

One female customer who seemed comfortable in Kozuchi's environment appeared to be in her mid-40s. She only needed a little more time for lunch than her male counterparts. She turned out to be a regular customer, who unlike other women, comes to the restaurant alone and eats without talking. Apparently, she orders the teishoku of the day almost every time she comes. Oishi says he welcomes this type of female customer.

This suggests that Kozuchi or Mimura may not be trying to preserve any ideal of culinary male chauvinism at all. As long as the concept of quick eating and no talking is adhered to, teishoku-ya actually provide great places for enjoying traditional home cooking, be the customers male or female.

(This article was written and posted on March 13, 2004)